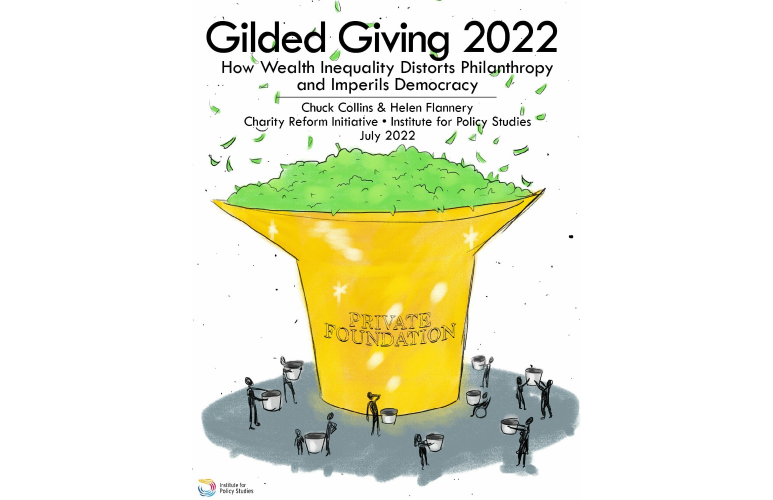

The ultra-wealthy, who are overrepresented among funders as revenue from smaller donors shrinks, reap disproportionate tax benefit and have an outsized hand in setting nonprofits’ priorities, according to authors of a new report.

The disproportionate influence stems from when their donations actually reach mission-focused, working charities. But, not all contributions do. The ultra-wealthy also take advantage of tax benefits and structures, such as being able to claim deductions while parking money in foundations and donor-advised funds (DAFs), without directly contributing to social good, according to authors of Gilded Giving 2022: How Wealth Inequality Distorts Philanthropy and Imperils Democracy.

The headwinds against smaller donors have only increased during the past few years. Changes to the tax code that damp charitable funding, along with historically outsized returns in investments, have also sapped the initiative for those without excessive means to donate.

“Without intervention, ultra-wealthy philanthropists will continue to divert more and more charity dollars from operating profits and will rival state and local governments in their ability to shape public policy in their interest,” wrote Institute for Policy Studies Director of the Program on Inequality and the Common Good Chuck Collins and Associate Fellow Helen Flannery, who co-authored the study.

The report offers a bleak picture of the current state of U.S. giving. During the past two decades, the percentage of households that donate has dropped — from 66% in 2000 to 50% in 2018, the most recent year of data used for the report. The drop corresponds with increasing financial insecurity, as reflected in employment levels, homeownership rates and wages.

The decline in charitable donations sped up under the 2017 passage of the Tax Cuts and Job Act, which raised the threshold for non-itemized deduction claims. Before the bill was passed, 25% of taxpayers itemized their charitable giving. By 2018, after the bill had taken effect, only 10% did so, a figure that slipped further to 9% in 2019. According to the report authors, the slippage was most prominently seen within households earning between $50,000 and $400,000 annually.

Concurrently, high-income households have been claiming an ever-increasing percentage of charitable deductions. During the early 1990s, households with annual incomes in excess of $200,000 claimed less than 25% of charitable deductions. As of 2019, those in the same income group — admittedly a somewhat larger share, due to inflation if nothing else — claimed two-thirds of deductions. And those even further up the income ladder saw greater increases in their deductions: households with $1 million in annual income made 10% of charitable deductions in 1993 but 40% in 2019.

Again, however, these funds are often not making it into the coffers of mission-based, working charities. More often, a donor’s private foundation or a DAF received the contributions, allowing the funders to claim deductions while having the ego stroke of watching their potential for giving grow without acting on it. The percentage of funds going into these structures is increasing: private foundations have seen their take increase from 6% in 1992 to 15% of all donation activity today, while contributions to DAFs jumped from 4% in 2007 to a similar 15% today.

Because a greater concentration of total donation amounts is from a small circle of elite funders, these funders wield disproportionate influence over charities’ activities, and even their core missions, thereby endangering the clients who depend on the charities’ work, as well as the charities themselves, according to the report authors.

The authors include several proposed reforms, including:

- Requiring DAFs to pay out the entirety of donations within three years of the donations going into the fund. Payouts would include all income earned on the donations during their time in the DAF.

- Holding tax deductions for the donation of complex assets to their sales value, thereby avoiding inappropriately inflated assessment of non-cash appreciated property such as artwork, cryptocurrency and real estate.

- Increasing DAF transparency, including public disclosure of and reporting on DAFs on an account-by-account basis. If implemented, this could be structure to protect anonymous givers.

- Increasing the minimum annual foundation payout level from 5% of the average market value of its assets to 10%.

- Excluding administrative overhead and grants to DAFs from a foundation’s minimum payout requirement.

- Replacing the current itemized charitable deduction with a universal charitable tax deduction for all households that contribute more than 2% of their adjusted gross income to charity.

- Establishing a lifetime cap on charitable gift deductions, which would prevent ultra-wealthy donors from manipulating charitable giving to reduce their tax burden indefinitely to zero. The report authors suggest a lifetime cap of $500 million for charitable tax deductions.

- Creating a cap for charitable estate tax deduction, to avoid limitless amounts of money a person can pass tax-free to charity within their estate. Report authors recommend capping estate tax charitable deductions to 50% of the donor’s estate value.

- Levying a “wealth tax” of 2% on DAFs and closely held private foundations that have assets in excess of $50 million. The tax would apply to all DAFs and private foundations managed by their founders or family members.

A full copy of the report is available here: https://ips-dc.org/report-gilded-giving-2022/