HR managers focusing on staff retention as pool of workers tightens

Nonprofit executives might have been a bit tentative about leaving their jobs or retiring in the wake of the Great Recession a decade ago. Their retirement plans and stock portfolios were decimated. They were probably faced with difficult organizational decisions about staffing and cutting expenses.

Things are different at the dawn of 2020. The economy continues to chug along, despite some concerns about another possible economic blip, while the unemployment rate remains at historic lows. Baby Boomers are probably more likely to move on, with fewer Gen Xers to fill those executive posts while a whole new generation of Millennials has come of age in the nonprofit sector. There’s also Generation Z now beginning to break into a bountiful job market.

Turnover among full-time employees was an average 12.3 percent in the most recent Nonprofit Organizations Salary and Benefits Report from The NonProfit Times and Roswell, Ga.-based Bluewater Nonprofit Solutions. Turnover was highest, between 16 and 17 percent, among organizations with budgets of $5 million to less than $50 million, which spanned three categories.

Almost half of respondents to a recent survey by Nonprofit HR said they will seek new or different employment during the next five years, and 23 percent of those said that nonprofits would not be among the types of organizations they intend to pursue.

Of those who indicated they would not work for a nonprofit, the number one reason cited –by 49 percent of them –is that nonprofits do not pay enough. Almost one in five (19 percent) said it’s because nonprofits don’t offer good long-term career opportunities. About one in eight (12 percent) said that nonprofits are “not well-run businesses.”

The Nonprofit HR survey was administered to more than 1,000 respondents with the help of a market research firm. More than 60 percent of respondents were employed either full-or part-time, and of those 12 percent worked for a nonprofit at the time.

“Gone are the days of talented professionals being willing to take a vow of poverty to work for a cause or a mission they are passionate about,” Nonprofit HR CEO Lisa Brown Alexander said. The social sector, she said, has long faced the misperception of being low-paying with limited opportunities for professional growth. “These statistics are alarming and should serve as a warning to social impact organizations of all types who have not adapted a talent attraction strategy to remain competitive,” she said.

Social enterprises, such as for-profit companies for social causes, with higher brand visibility are attracting talent that would historically have sought mission alignment with nonprofits, according to the data. Nonprofits can connect with current and potential future talent by communicating how they impact communities they serve, their unique benefits and by emphasizing monetary and non-monetary rewards.

“What we’re seeing in the preliminary data, at least right now, people are leaving the sector, not in droves necessarily, but they’re leaving for specific reasons around pay issues, compensation and benefits,” said Patty Hampton, CSP, vice president and managing partner at Nonprofit HR, based in Washington, D.C. “There are some nonprofits that are really just not structured, not running themselves like a business,” she said.

“There are a lot of people leading nonprofits who are retiring and so there are opportunities now — and a lot of them.” – Jennifer Dunlap

People are feeling more confident around leaving organizations, specifically nonprofits, and might be changing careers as well, according to Hampton. “We’re seeing a lot of these organizations are historically run by leaders, executives who are aging out in terms of they are readying to leave,” she said.

“We’re going through that generational shift of leadership at nonprofits,” said Jennifer Dunlap, co-founder and president and CEO of DRi (Development Resources Inc.), an Arlington, Va.-based executive search firm. “There are a lot of people leading nonprofits who are retiring and so there are opportunities now — and a lot of them — for talented people,” she said. Combine that with a good economy and nonprofits doing well in recent years and it’s a very competitive market for good leadership at nonprofits. “For a talented individual, you have a lot of opportunities,” she said.

The average tenure of a chief executive officer or executive director was almost 13 years, according to the most recent Nonprofit Organizations Salary and Benefits Report from The NonProfit Times and Bluewater Nonprofit Solutions. It was less than eight years among the smallest nonprofits (less than $500,000 operating budget), and longest among the second-largest category (between $25 million and less than $50 million), at more than 18 years.

While that kind of market can influence salary levels, nonprofit leaders also are wisely starting to look at the entire compensation package and not just salary, according to Dunlap. That includes doing more things such as performance-based bonuses, so if an executive director grows an organization — or whatever the board lays out as key performance indicators — they can be additionally compensated.

“That’s very smart. It’s a way to protect out-of-control salary escalation, and being true to key financial stewardship of donor money that they need to have,” Dunlap said. “They can still attract talent, compensate at the right level, but only if they’re really performing,” she said.

Retention bonuses also are becoming more prevalent, not just in higher education where it’s more common but among nonprofits generally, and not just at the executive director level but lower leadership posts as well, according to Dunlap.

“We all know turnover is a chronic problem and it harms organizations,” Dunlap said, which is why incentives to reward employees for reaching a certain number of years at the organization are becoming more popular.

“It’s become much more of a focus to really keep the talented people,” she said, adding that those that do it well see “exponential growth” and are recognized as top charities.

There’s definitely been turnover within the C-suite in recent years, according to Dunlap, with typical turnover in fundraising and less turnover in programming positions. “Certainly at the executive leadership level and probably some turnover in HR leadership because nonprofits are demanding more of their HR people,” she said. “I’ve never seen a market like this. There are so many jobs out there,” Dunlap said, estimating some five openings for every one good fundraiser.

Digital marketing is a growing piece of many organizations that hasn’t been staffed correctly, Dunlap said. “It’s a matter of learning, how they should be using, why, what’s the right segment to focus on, what’s the right growth rate. It’s kind of new for a lot of nonprofits,” she said. “They’re all still trying to figure out how to use the medium correctly to inspire and engage donors, as well as actually raise money that way, or if they need to be one tool and complement other fundraising activities. It’s different for every organization,” she said.

To make the best offer to prospective employees, the compensation plan must stay competitive, taking into account the whole picture: vacation time, telecommuting options, and of course, salary. However, small nonprofits are having a hard time competing, according to Nurys Harrigan-Pederson, president of CareersInNonprofits, a nonprofit recruiting agency headquartered in Chicago, with offices in Washington, D.C. and San Francisco. “They still want to attract talent purely by who they are as their mission. That’s very hard these days. You have to compete on more than that,” she said. It used to be the mission and the name of a nonprofit would be enough to attract candidates. But, people are interested in more than one cause. They’re being lured by nonprofits that can compete so small organizations are losing talent. “I see it over and over again, making one or two offers but being declined,” she said.

Sometimes it depends on the size of a nonprofit, Harrigan-Pederson said, as she finds that organizations that are medium to larger — anything more than $10 million in budget size — are more aware that they have to become competitive to attract talent. “In this market, there are more jobs than there are candidates,” she said.

Signing bonuses for prospective job candidates are becoming more popular, according to Harrigan-Pederson. She estimates that about one nonprofit client a year, among 300, would offer a signing bonus. Now, it’s probably close to 10 percent of her clients where a signing bonus is offered. A signing bonus can provide some flexibility since it’s a onetime payment and not part of the annual salary, Harrigan-Pederson said.

“A good trend we’re seeing with nonprofits we’re working with across the sector is mid- to large and mega nonprofits are being more comfortable with performance-based incentives,” Hampton said. “They’re now realizing to get the right executives on board they’re providing an incentive bonus,” she said, of up to $20,000 to $30,000 based on performance. Once the candidate is on board, they meet with the search committee and/or board to develop a plan to move forward, she said.

Even smaller organizations — those with budgets of less than $20 million — are becoming more comfortable with signing or retention bonuses, too, whereas before they didn’t really have the budget to do that, Hampton said. Some recruiters and executive search consultants are now faced with giving people a salary range, making sure they dig a little deeper so they know that the position isn’t just about salary but about mission, culture and vision for the organization — and, of course, fundraising.

“They still want to attract talent purely by who they are as their mission. That’s very hard these days.” – Nurys Harrigan-Pederson

“Fundraising has always been a part of an executive leader’s portfolio, but more so now, some have to come on board, and fundraise to pay for their own salary,” she said.

Leaders at medium and large nonprofits have always been comfortable offering bonuses, Hampton said, but now they’re finding they have to compete with other organizations, or even for-profit and social- enterprise organizations.

Nonprofit recruiters are showing they’re paying attention, according to Hampton. Nonprofit HR’s data shows about 52 percent are now focused on compensation and benefits because they see that as a retention tool to get people on board.

It’s about different perks, too, such as wellness, Hampton said, because people are focusing more on that. There’s a movement no longer about just work-life balance but work-life integration. People are taking that into consideration and educating their staff, Hampton said. “What can you provide to your team of people within the organization that they spend close to 12- to 14-hour days in the organization,” she said.

The primary reason for voluntary turnover at nonprofits was the lack of opportunity for upward mobility and career growth (60 percent), followed by compensation and benefits (48 percent), according to Nonprofit HR’s survey results.

Almost 65 percent of respondents to the 2020 Nonprofit Talent Management Priorities Survey said they have no formal talent management strategy. However, more than half of organizations surveyed said they prioritizing compensation and benefits, with the top three strategies being talent acquisition, culture and engagement, and performance management.

More than three-quarters of nonprofits use short-term incentives (STIs), and median spending on them is about 2 percent of operating budget at median, according to the 2019 Incentive Pay Practices: Nonprofit/Government Organizations survey by WorldatWork, in partnership with Compensation Advisory Partners (CAP).The most common types of STI plans are annual incentive plans (AIPs) and spot award programs, with discretionary bonuses, project bonuses, team/small-group incentives and profit- sharing plans in the mix.

The sixth edition of the joint research effort between WorldAtWork Total Rewards Association and CAP focused on the prevalence of short- and long-term incentive programs exclusive to U.S. nonprofit and government organizations. The survey revealed the top reward tools for retaining talent were a retirement plan, 60 percent; job advancement/ promotion, 47 percent, and flexible work arrangements, 43 percent. They are followed by culture/community, 35 percent, and additional base compensation, 33 percent.

Two-thirds of nonprofit and government organizations reported one or two STI programs in 2019 compared with three or fewer STIs being the prevalent practice in 2017. The types of plans used remained mostly consistent from 2017 to 2019, according to the survey. AIPs and spot awards were the most prevalent, approaching 80 percent in 2019, while spot awards and discretionary bonuses hovered on either side of 50 percent.

Less common were a project bonus and team/small-group incentives, each at 16 percent, and a profit-sharing plan, 4 percent, which was down from 10 percent in 2017. Median spending by nonprofits on STI programs was down about 2.3 percent from 2017, to about 2 percent of operating budget for 2019, which is expected to remain about the same for 2020.

“… mid- to large and mega nonprofits are being more comfortable with performance-based incentives.” – Patty Hampton

Among the 54 organizations that responded that they had an AIP, the top three objectives of such plans are to align incentives with short-term goals (70 percent), reward employees (69 percent), and focus employees on specific goals (50 percent). Less common goals included sharing the organization’s financial success with employees (31 percent), retaining employees (26 percent), being competitive with other employers (22 percent), and recruiting qualified employees (13 percent). The least common objective was providing special recognition (7 percent).

STI plans are being simplified as nonprofits are getting used to having these plans as reward tools. The prevalence of organizations using 10 or more performance measures in their AIPs decreased in 2019, and more organizations now report using four to six performance measures.

Long-term incentive plans (LTIs) are used by a minority, with 22 percent reporting an LTI plan in 2019.

“One of the most interesting trends this year is the decrease in the number of performance measures used by nonprofits,” said Bonnie Schindler, CECP, principal at CAP. “Four to six performance measures are now prevalent, reflecting a move toward more holistic but manageable incentive management frameworks. Discretion also continues to play a role in incentive decisions given the difficulty in measuring performance objectively without a true profitability metric.”

WorldatWork collected survey data for the two surveys from its members in June and July 2019. The survey report was based on 182 responses from private, for-profit companies and 116 nonprofit and government organizations. Demographics of the survey sample and the respondents are similar to the WorldatWork membership as a whole. The typical WorldatWork member works at the managerial level or higher in the headquarters of a large company in North America.

In tandem with incentives and bonuses, nonprofits are having conversations earlier with new hires, putting reviews into place within the first six months as opposed to a year, as traditionally has been the case. Employees are coming in knowing when the discussion will be taking place and what it takes to get an increase, Harrigan-Pederson said. “We’re helping clients set up realistic goals for employees to meet, and then determining the incentive,” she said, whether it’s a salary increase or a different benefit, such as more vacation time or more opportunities for telecommuting.

Harrigan-Pederson expects the marketplace to continue to be more competitive for top talent in 2020. “Nonprofits are going to have to get creative in who they hire,” she said, suggesting career matching or job designing. Recruiters might have to compromise when searching through job candidates. “They may not get who they want because of how competitive it is, but hire who they want, and a year or two from now, build that person up,” she said.

If an organization is looking for a candidate with three primary traits but doesn’t check off all the boxes, Harrigan- Pederson suggested it could be wise to get the candidate in, knowing that in 18 months or more, the person will have all those skills under their belt. “It’s all about keeping and attracting talent,” she said.

Among the biggest challenges for charities is not having a growth plan in place for employees, including an exit plan, according to Harrigan-Pederson. “Employment moves so fast. People are not making five-year career plans but two-year career plans,” she said.

Employers benefit from having growth plans in place and career mapping plans that can help attract and retain top talent because the workforce will be formed by Millennials. “Millennials are always on the move. If they don’t have something to look forward to, they get bored quickly and will jump ship,” Harrigan-Pederson said.

Organizations are finding that the workforce is changing as younger generations move up and into the sector. Dunlap described the workforce as more tech savvy, with more work-life balance requests that previous groups have not. “It’s understanding that it’s not just about the money,” she said. “There’s lots of ways to attract and retain talented people,” Dunlap said, and appreciation of them as an important part of the team is on way. “They’re the captains of their own careers. What that should mean for nonprofits is to do a couple of things, be much better at succession planning and growing people into positions,” she said.

Identify high-potential talent, like corporations do, Dunlap said. With the right training and coaching, five to seven years from now, that person could be a senior leader in the organization and deliberately cultivate that, she said. “Just like donors, it’s always better to take a talented person and help them fulfill their career up and in your organization rather than making them feel like they have to leave the organization,” Dunlap said.

Charities have historically suffered from an expectation that they should underpay their people, Dunlap said. “In reality, we should want the organization to be doing it right, however right is defined by the requirements of positions, skill set and size of the organization,” she said. “If compensation packages make the board uncomfortable, there’s a reason for that, but it needs to be an objective decision. You see the impact of having the right person lead it as opposed to the cheapest,” Dunlap said.

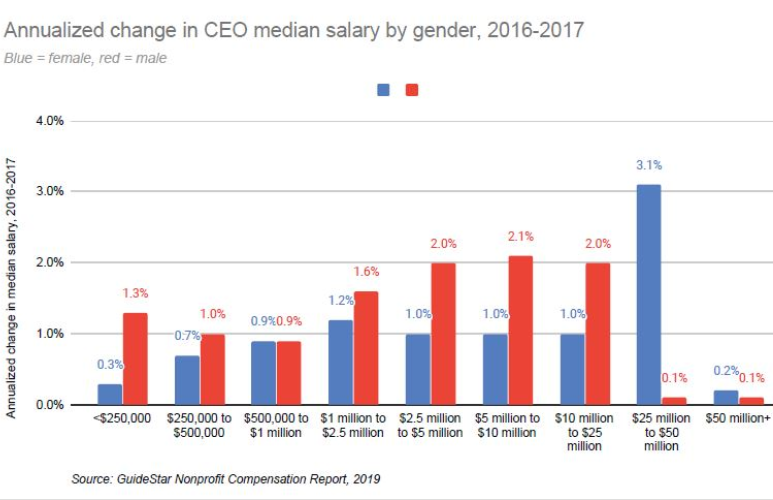

In 2018, incumbent CEO compensation increases in 2016 approached pre- Great Recession levels, according to the GuideStar Nonprofit Compensation Report. Only two years — 2015 and 2016 — saw increases of 4 percent or more.

A gender pay gap continued at all sizes of organizations but 2016 data showed the gap shrank a bit. Median compensation of female CEOs lagged those of male peers anywhere from 4 percent at the smallest organizations to 20 percent at the largest. That range was between 17 and 25 percent in 2005. While the percentage of women leading nonprofits has increased since that time, females were more likely to lead smaller organizations.

The 2019 report, which covers Fiscal Year 2017, showed median compensation increases for incumbent CEOs were lower than the previous two years. Gender gap ranged from 5 percent at smallest to 20 percent at largest in 2017.

The study analyzed compensation data reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) by 113,549 nonprofits and contains data on 162,853 individual positions. Incumbent compensation data was available for 106,252 positions at 79,910 nonprofits.

The number of organizations classified in the highest budget range of $50 million or more grew by 9 percent, according to Holly Ivel, senior director of business development, at GuideStar by Candid. There were two primary reasons for that. For one, organizations were growing and moving up from the lower budget band of $25 million to $50 million. The second driver was just the timing of tax filings, as a number of organizations had larger budgets in that reporting year (2017).

“The story seemed to be getting a little better last year,” Ivel said, relative to women’s salaries, kind of stagnated.

Incumbent categories showed higher median increases for women than men. If the person was in a position year-over-year, women were getting a slightly larger bump in median salary in all but the top two budget bands. It wasn’t huge but at least it skewed slightly larger for women in those incumbent positions than men to narrow a long-time gap.

The number of women running large organizations remained pretty flat. “It’s not an exciting trend but the reality is the number of women leading organizations, the percentage of women goes down as an organization gets larger,” Ivel said. Females share equally in leadership roles at nonprofits until organizations reach about $2.5 million budget level. “Once an organization gets bigger than that, the percentage of women leading larger organizations steadily declines by each budget band,” she said.

In GuideStar’s 2018 report, there were about 159,000 observations, of which about 91,000 were incumbent, or 57 percent. Last year’s report indicated about 65 percent incumbent.