Charitable giving set another overall record in current dollars for 2018 but giving was uneven throughout the sector under new federal tax laws. A boost from foundations and corporations was unable to overcome the first decline in individual giving since 2013.

The $427.71 billion in overall giving last year is 0.7 percent more than the revised $424.74 billion for 2017 but down by 1.7 percent when inflation is taken into account, according to preliminary estimates from “Giving USA 2019: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2018,” released this morning. Adjusted for inflation, the $435.11 billion in giving in 2017 remains the highest ever calculated.

The longest-running and most comprehensive report of its kind in America is published by Giving USA Foundation, a public service initiative of The Giving Institute researched and written by the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University/Purdue University (IUPUI) in Indianapolis, Ind.

Individual giving was down 1.1 percent, or 3.4 percent when adjusted for inflation, the first time it’s dropped since 2013 and only the second time during the past decade. As a percentage of the total giving, individual giving tumbled to 68 percent, the first time it’s been below 70 percent since 1954. Individual giving was 1.9 percent of disposal personal income, in current dollars, and 2.1 percent of the inflation-adjusted $20.49 trillion Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

“As we’ve seen in previous years, the strong economy had a positive influence on individual giving; however, these positive effects may have been tempered by policy changes and other factors to create a more mixed picture for giving in 2018,” said Una Osili, Ph.D., associate dean for research and international programs at the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. “We have strong historical data about the link between economic variables, the stock market and charitable giving, and we will be analyzing data for the next few years to better understand how broad giving patterns may have changed,” she said.

It’s the first estimate of giving under new federal tax changes approved in late 2017 for the 2018 tax year. Tax changes approved in late 2017 doubled the standard deduction, reducing the number of taxpayers eligible to itemize from more than 45 million to fewer than 20 million. Households where taxes are itemized account for the vast majority of individual giving and that might have played a part in the drop in individual giving last year, the first under the new federal tax laws.

Giving by foundations and corporations reached record levels but still was still just one-third, by comparison, of the $292.09 billion given by individuals. Giving by foundations was up 7.3 percent to $75.86 billion, or 4.7 percent inflation-adjusted, reaching its highest-ever share of giving at 18 percent. The last time foundation giving declined was in 2010. Giving by corporations was up 5.4 percent, eclipsing $20.05 billion, or 2.9 percent when inflation is taken into account. It remained 0.9 percent of pre-tax profits for the fourth consecutive year.

Bequest giving was essentially flat, at $39.71 billion, compared with $39.69 billion in 2017, but when adjusted for inflation declined by 2.3 percent.

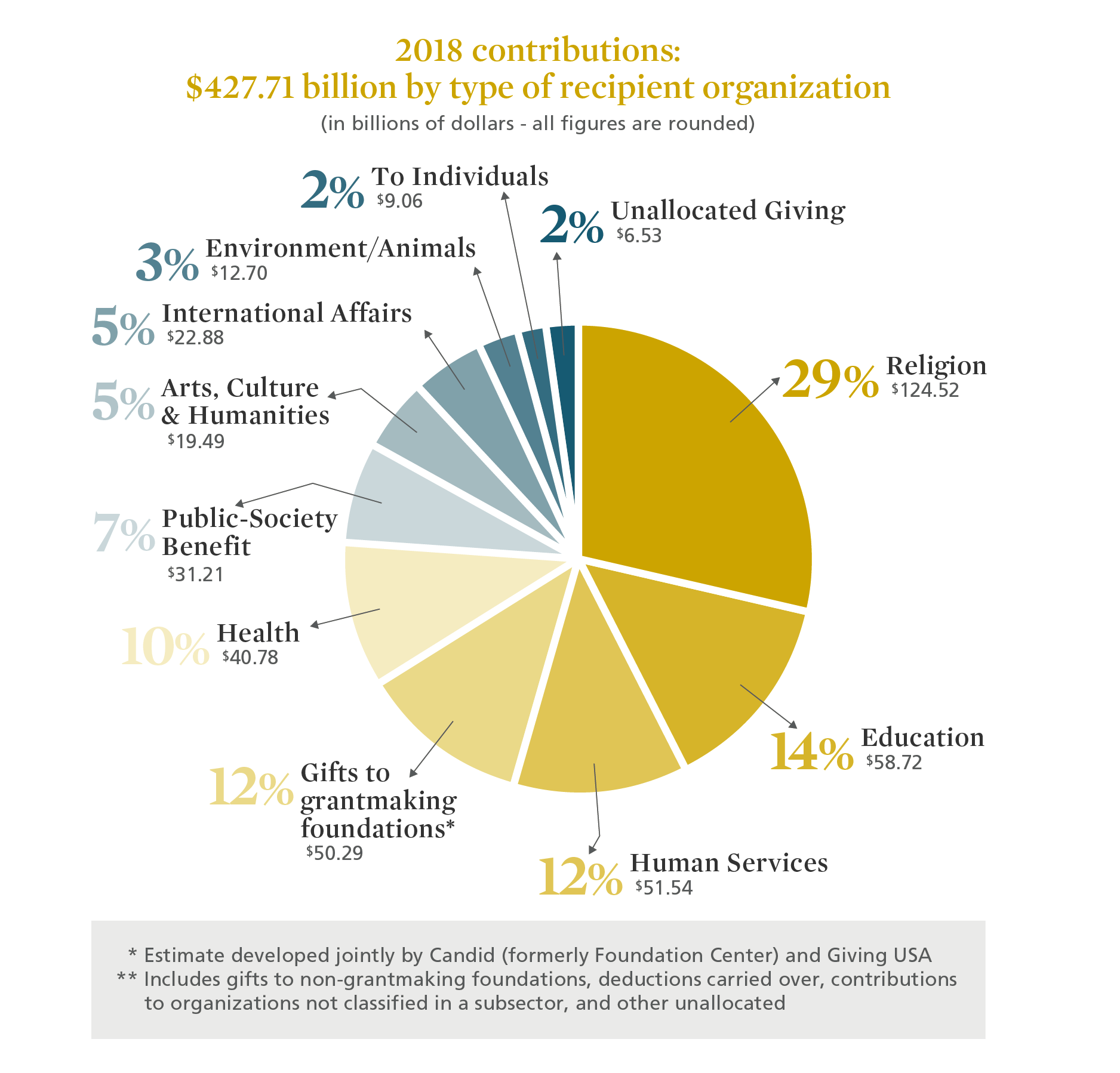

Giving was uneven throughout the sector, with most areas being flat or down in 2018, unable to keep pace with inflation:

- Health, +0.1 percent, -2.3 percent when adjusted for inflation, $40.78 billion;

- Arts, culture and humanities, +0.3 percent, -2.1 percent adjusted, $19.49 billion;

- Human services, -0.3 percent, -2.7 percent adjusted, $51.54 billion;

- Education, -1.4 percent, -3.7 percent adjusted, $58.72 billion;

- Religion, -1.5 percent, -3.9 percent adjusted, $124.52 billion; and,

- Foundations, -6.9 percent, -9.1 percent adjusted, $50.29 billion.

Only two subsectors saw growth of any significance last year:

- International affairs, +9.6 percent, +7 percent adjusted, $22.88 billion,

- Environment and animal, +3.6 percent, +1.2 percent adjusted, $12.7 billion.

Unallocated giving, the difference between giving by source and use in a particular year, was $6.53 billion.

“Despite declines in 2018, many subsectors experienced their second-best year for giving ever, when adjusting for inflation,” said Laura MacDonald, vice chair of the Giving USA Foundation and founder of Benefactor Group in Columbus, Ohio.

Preliminary estimates for 2017 giving, released in June 2018, were revised up from $410.02 billion to $424.74 billion. Giving USA will finalize those numbers in June 2020, after data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) are received. Total giving for 2016 was revised a second time and finalized in this report at $396.52 billion and $414.86 billion when adjusted for inflation.

The Sierra Club had one of its biggest years ever in 2017 so a return to normal was likely for 2018. End-of-year (EOY) giving tracked with the S&P and online revenue proportionally comes in during December. “What we saw was some real concerns in the middle of the month, like a lot of other people did,” said Mary Nemerov, chief advancement officer, pointing to the stock market volatility in December 2018. “The type of people who make $100, $500 or $1,000 end-of-year gifts were really feeling that anxiety,” she said.

Sierra Club ended the year with a strong couple of days. “Response rates were not as great as what we had anticipated but we ended up fine because folks did sort of come back and make their gifts at the end of the year,” she said.

The Oakland, Calif.-based organization saw a huge surge of giving from donor-advised funds (DAFs), according to Nemerov, and not just from donors making large $25,000 distributions but in the hundreds of dollars. “People who make a number of midsized gifts — between $100 and $1,000 — now are using DAFs to do that,” she said, wondering how much might be a response to the uncertainty of tax reform. Some observers had anticipated donors might bundle donations in a particular year to qualify for itemizing deductions. “Or it’s just that more people are opening DAFs,” Nemerov suggested. She estimated at least $1 million in unanticipated gifts were from DAFs, much of it at a mid-level range.

After the 2016 presidential election, Sierra Club tripled its number of monthly donors from 35,000 to more than 100,000. Retention has been pretty good and consistent, according to Nemerov, with those joining after 2016 typically staying on the file for two years. “Once they get locked into monthly giving, even $10 a month, that provides us with a lot of organizational stability. It’s easier to retain that person year-over-year rather than give $39 or $59 once a year and having to email and renew that annual gift,” she said.

“Nationally, retention was down but giving was up, our numbers reflect that,” said Sarah Valentine, vice president of development at the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, Wash. “Retention was down but overall numbers were up. It’s makes me scratch my head a little bit,” she said.

Nevertheless, it was a record fundraising year for the zoo, thanks to a handful of estate gifts. The zoo typically gets between $1 million and $2 million in bequests but last year received some $7 million, including $5 million from an extraordinary donor who passed away last year and gave a number of gifts to local nonprofits.

“We’re seeing that trend with the wealth transfer starting to happen,” Valentine surmised. It was probably the largest endowment gift the zoo has ever received, along with a couple of other estate gifts, including one from a woman who wasn’t even in their donor database.

“We’re one of those organizations people grow up with, so even if you’re not a donor, my theory is, even though she wasn’t active with us, she had some special memory of the zoo and wanted to provide those types of memories for our kids. It’s the best explanation for it. She didn’t have a family and her estate planner couldn’t get an answer,” Valentine said.

Many of the zoo’s bequests are unrestricted but policy stipulates that the first $400,000 automatically be designated to the endowment. Anything beyond that is designated by the board. Donors often designate gifts to capital, like a new exhibit, or things like animal care, which gives the zoo latitude in how best to direct the funds, Valentine said.

The annual giving program saw a boost from a new exhibit that brought rhinos to Seattle for the first time ever. “It was a new and compelling opportunity for our donors to really make a difference with our annual giving,” Valentine said. A lot of donors who typically give less than $1,000 went above that with a special donor recognition, getting their name on a peacock feather within the exhibit for $1,000 gift. “It pushed our annual fund donors,” she said.