Typical five-year strategic planning forecasts perform about as well as dart-throwing chimpanzees, according to recent cognitive neuroscience research.

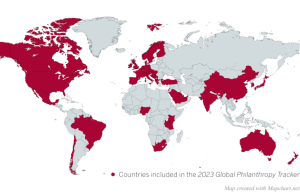

The operations director at a mid-size nonprofit, let’s call her “Linda,” wasn’t surprised when she learned about these new studies. In 2011, her nonprofit went through a five-year strategic planning process, which resulted in a major commitment to growing the organization’s international outreach.

Well, the plan didn’t go according to plan. Political and social developments associated with the turbulent 2016 political season caused a great deal of uncertainty and resulting problems for this international expansion. The assumptions built into the strategic plan, and the resulting projects and financial commitments, failed to pan out, with serious negative consequences for the nonprofit.

For example, the plan resulted in a major investment into expanding international facilities and staff in several new countries. Yet, the drastically shifted political environment meant that these new ventures could no longer function effectively.

Several major institutional funders withdrew their planned gifts, while private donations plummeted. “Linda,” a real executive whose identity is being protected, had to make very serious cuts to keep key operations running. She ended up not only terminating the new ventures and staff, but also some well-established ones. She had to cut some other planned projects and lost the initial investments. She also had to lay off long-time staff to maintain the nonprofit’s financial viability.

It’s not a pretty picture. It is no wonder she wasn’t optimistic about strategic planning.

The Problems

Strategic planning at “Linda’s” nonprofit suffered from a number of dangerous judgment errors that result from the biological structure of our brain, what scholars term cognitive biases.

Research indicates that cognitive biases pose a high threat to strategic planning. Linda’s plan, in particular, suffered from the planning fallacy, our tendency to assume that everything will go according to plan. That dangerous judgment error leads to the failure to build in enough resources and flexibility for various contingencies.

Linda’s plan also exhibited the mental blind spot known as the optimism bias. It’s like it sounds: the optimism bias causes us to perceive a more bright and hopeful vision of the future than is the case in reality. We then underestimate threats and risks.

Finally, the plan proved highly vulnerable to sunken costs. This cognitive bias makes us reluctant to terminate projects after we already sunk some money into them.

Due to the strategic plan’s structure, Linda’s organization continued to throw good money after bad long after many red flags suggested it might be time to cut the losses on the projects. As a result, the nonprofit suffered substantially more losses than needed, making the required financial corrections significantly more painful than needed.

Fortunately, there’s a much more effective 10-step method to strategic planning that incorporates cutting-edge neuroscience research on how to defeat cognitive biases. Rather than making a simple strategic plan, you focus on assessing potential threats and opportunities and build them into your plan. You emphasize making your plan flexible and resilient, able to handle unanticipated developments when you made the original plan. You also work to counteract the typical cognitive biases that cause your plans to go astray.

Step 1: Scope and Strategic Goals

Decide on the scope and the strategic goals of the activity that you will evaluate, as well as the timeline, anywhere from six months to five years. Remember that your forecasting will deteriorate the further out you go as you make longer-term plans, so add extra resources, flexibility, and resilience if you have a longer projected timeline. For the same reason, make your strategic goals less specific and concrete if you have a longer time horizon.

Step 2: Gather

Gather in a room the people relevant to the activity that is being evaluated, or, if there are too many to have in a group, representatives of the stakeholders. A good number is six, and not more than 10 people to ensure a manageable discussion. Make sure the people in the room have the most expertise in the activity being evaluated, rather than simply gathering the higher-ups.

The goal is to give input on various attributes of a vision of the future and then address any potential problems and opportunities uncovered. At the same time, have some people with the power to make and commit to the decisions that will be reached during the exercise.

Step 3: Explain

Explain the exercise to everyone by describing all the steps, so that all participants are on the same page about the process.

Step 4: Your Anticipated Future

Consider what the future would look like if everything goes as you intuitively anticipate and how many resources it would require.

Step 5: Potential Internal Problems

Consider what the future would look like if there were unanticipated problems internal to the nonprofit that seriously undermined the expected vision of the future. Write out what possible problems might arise and evaluate the likelihood and impact of each one.

Assess the resources (money, time, social capital) that might be needed to address these problems in alternative visions of the future. Try to convert the resources into money if possible in order to have a single unit of measurement.

Next, think about what you can do to address the internal problems in advance, and write out how much you anticipate these steps might cost. Finally, add up all the extra resources that might be needed due to the various possible internal problems and all the steps you committed to taking to address them in advance.

Step 6: Potential External Problems

Complete the previous step for potential problems external to the nonprofit organization’s activity.

Step 7: Potential Opportunities, Internal and External

Go on to consider what your anticipated plan would look like if unexpected opportunities opened up. Most opportunities will be external, but assess internal ones as well. Next, evaluate the likelihood of each scenario and the number of resources you would need to take advantage of this opportunity.

Discuss the steps you can take in advance to take advantage of unexpected opportunities and write out how much you anticipate these steps might cost. In the end, add up all the extra resources that may be needed due to unexpected opportunities and all the steps you committed to budgeting to take advantage of these potential opportunities.

Step 8: Check for Cognitive Biases

Check for potential cognitive biases that are relevant to you personally or to the organization as a whole and adjust the resources and plans to address such errors.

Step 9: Account for Unknown Unknowns

To account for unknown unknowns — also called black swans — add 40 percent to the resources you anticipate. Also, consider ways to make your plans more flexible and secure than you intuitively feel is needed.

There are major disruptors, such as the collapse of the 2008 housing bubble and the Great Recession, and prior to that, the dotcom boom and bust. Given the current political turbulence, reserving 40 percent makes sense.

Step 10: Communicate and Take Next Steps

Communicate effectively to organizational stakeholders about the additional resources needed. Then, take the next steps that were decided on during this exercise to address unanticipated problems and take advantage of opportunities by improving your plans and reserving resources.

Gleb Tsipursky, Ph.D., is chief executive of Disaster Avoidance Experts in Columbus, Ohio. He is the author of “Never Go With Your Gut: How Pioneering Leaders Make the Best Decisions and Avoid Business Disasters.” He received his Ph.D. in the History of Behavioral Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2011 and a Master’s Degree at Harvard University in 2004.