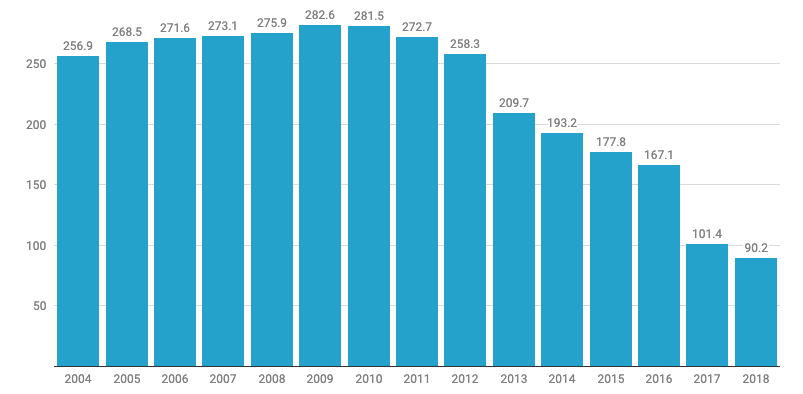

Workplace giving by federal employees through the Combined Federal Campaign (CFC) declined for the ninth consecutive year, down 11 percent in 2018.

Pledges totaled $90.2 million while volunteer time was more than 116,000 hours, valued at $2.7 million, for a total equivalent of $92.9 million, down from an aggregate $104.3 million in 2017.

The drop in giving follows a decline of 39 percent in 2017 — a combined 46 percent since the Office Personnel Management (OPM) implemented a new system two years ago. The 39-percent collapse in 2017 was the largest decline in CFC contributions in at least the past decade, dropping from $167.3 million in 2016 to $101.4 million.

More than 79 percent of participating federal employees pledged electronically during the 2018 campaign, about $71.7 million, with the remaining 21 percent, or $18.5 million, using traditional paper pledge forms or sending a check. The CFC eliminated cash and special event contributions.

Donor participation in the CFC by federal employees dropped by more than half in 2017 and continued to decline in 2018, down from 4.1 percent to 3.9 percent.

“Due in part to an earlier start, donor contributions for 2018 were trending ahead of 2017. However, after the peak on Giving Tuesday, the threat of an actual lapse in appropriations affected the campaign,” Keith Willingham, director of the Office of Combined Federal Campaign, said in an email to “CFC stakeholders” on Monday.

OPM Acting Director Margaret Weichert extended the campaign through Feb. 22 because of the 35-day government shutdown. An additional $17.6 million was pledged after Jan. 11. “These contributions made up some of the gap that opened up in late December and January during the government shutdown,” Willingham said in his message.

“You have to go back to the 1970s to see CFC giving this low,” said Steve Taylor, senior vice president of public policy at United Way Worldwide in Alexandria, Va. “The loss in giving impacts the entire sector.”

When CFC funding goes down dramatically, Taylor said many smaller charities, like food pantries and shelters, turn to United Way to help make up the difference. “More importantly, CFC was historically the single-largest source of private donations to most charities,” he said. “It’s on track to be gone in a couple of years. It’s really a sector-wide issue.”

Others aren’t as pessimistic. Until the government shutdown in December, the CFC was trending higher than the previous year, according to Patrick Maguire of Larkspur, Calif.-based Maguire/Maguire, Inc., an association management firm that is contracted by OPM to provide local operation marketing support for campaigns. “Many of the kinks from year one of the redesign had been worked out, and there was a good bit of leadership enthusiasm,” he said via email.

“Had it not been for the shutdown there was every reason to believe year two was going to surpass year one and reverse the downward trend,” Maguire added. An earlier start to the 2019 campaign will give outreach coordinators in the field more time to organize, making him cautiously optimistic about next year.

Jim Starr, president and CEO of America’s Charities, believes the host of radical, significant changes drove a lot of the decline in 2017 and is optimistic going forward because of improvements to the online system this past year and more focused activities for engagement. The Chantilly, Va.-based membership organization works with 130 charities.

Costs to run the CFC program remained more than $26 million for the second consecutive year. A five-page Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) document from OPM noted that fees charged by the CFC are less than the 35 percent threshold recommended by the Better Business Bureau Wise Giving Alliance, and that costs incurred for both systems are “on par with the costs of operating the paper only and paper-hybrid systems from before 2017.” The distribution fee last year was 19.8 percent, up from 16.5 percent.

Campaign administration was the highest cost, at $12.74 million last year, up from $12.39 million, followed by campaign promotion at $10.96 million, up from $10.87 million.

“CFC System Development,” which entails building an app and electronic giving systems, totaled $2.786 million, up slightly from $2.764 million. That cost is amortized for three years, with the final payment due in 2020. Once capital development of the system is completed, OPM expects expenses to drop, according to the FAQ document.

There are fixed contracts with five entities to support the campaign: Kaptivate, LLC; Maguire/Maguire, Inc.; Penngood, LLC; The Nolan Group; and, Tribal Tech, LLC.

In its FAQ document, OPM cited several steps it’s taking to increase donations and participation in the annual campaign, including:

- Research;

- Focusing efforts of outreach coordinators in campaign management and marketing “that makes the biggest return in attracting potential donors and charities;”

- Continuing to monitor the online donation system to make it safe, secure and easier to use;

- Increase training for campaign workers and federal leadership to improve the quality of campaigns in each CFC zone; and,

- Solicit federal retirees for gifts and for pledges of volunteer time.

“Among the many bright spots in giving was the growth in popularity of giving by federal annuitants and military retirees who contributed $1.5 million, more than triple the giving level from 2017,” Willingham said in the email. An executive order in 2015 allowed OPM to solicit retirees.