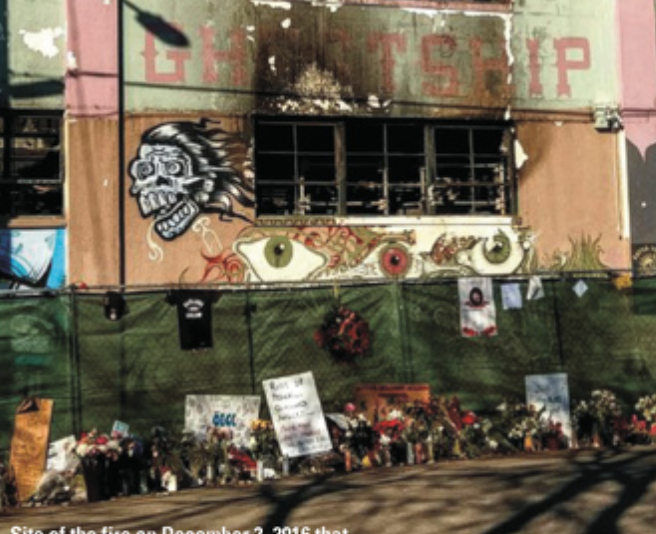

Oakland, California remains in mourning after a late-night warehouse fire on December 2 killed 36 people. The warehouse had been converted into an artist collective and housing units — both contrary to area zoning.

While the fire has shone a spotlight on the deficiencies and challenges surrounding affordable housing in the Bay Area and the nation at large, little comes as a surprise to Gloria Bruce, executive director of East Bay Housing Organizations (EBHO).

The Bay Area is currently in the midst of a housing squeeze, according to Bruce. “People of limited means have struggled to afford housing for decades, but it’s really at a different scale right now,” she said. “People are having to make compromises in order to afford a place to live.”

Housing in Oakland specifically, where EBHO is based, has grown worse in recent years, Bruce said. The city has been long thought of as the more-affordable counterpart to San Francisco, where so long as one had a job, the rents were relatively affordable. Prices are skyrocketing near an average of $2,500 per month now. A line has been created in which individuals priced out of San Francisco move to Oakland and now people are being priced out of Oakland.

This has been a frustrating development for natives who have lived through years of disinvestment only to see the city garner positive attention as the cost of living climbs. It has also created a challenging predicament for public officials who must now balance investment with a desire not to displace long-time city dwellers.

It is not all positive for incoming residents, Bruce said. Even if some in the tech industry — which is one cause of the housing boom in Northern California — are high earners, many aren’t well compensated and even those who are cannot sustainably spend the majority of their income on rent, she added.

EBHO has responded through advocacy and campaigning. The Bay Area suffers from a lack of homes and those that are being built are at market rate, not for seniors, veterans and individuals with lower incomes. In an effort to strike a balance, affordable housing funds have been established in municipalities, requiring a fee for not constructing affordable units along with those at market rate. Oakland recently adopted such a policy and EBHO is working to spread the concept to neighboring cities.

Efforts have also been made to educate tenants concerning their rights, rent control measures and voting interests. Six tenants’ rights issues were on Bay Area ballots this past November, Bruce said. “The crisis for safe and affordable housing didn’t start on December 2,” the day of the fire, she said. “People are heartbroken that it has come to this. People have been saying for a long time that a lack of safe affordable housing can mean lives. …We now see this in the most tragic way.”

EBHO is not involved in code enforcement, however, which has been called a contributing factor to the lives lost in the fire. Ratcheting up inspections is not a simple solution, Bruce said, as there is fear in the community that more stringent regulations would lead to evictions from imperfect, but otherwise safe, housing options.

Bruce said that there is plenty of misinformation surrounding housing at the moment and that a lot of work has to be done at the local level with limited overarching national policies. It will be for the nonprofit sector to help lead change and awareness, she predicted. “The big agenda for nonprofits out there is that we really need to do a better job of getting housing and urban issues to be part of the national discussion, because they aren’t right now,” Bruce said.

The Bay Area is far from the only place hurting from a housing crunch, according to Jane Graf, CEO of Mercy Housing, headquartered in Denver, Colo. Midwestern cities such as Chicago and Milwaukee are suffering from a lack of affordability, but the average family making a decent living can still find a home. That same concept is exacerbated on the coasts where it is near impossible to buy and difficult to even rent on moderate incomes in cities like Seattle and San Francisco where the pressure reaches further up into the upper middle class.

In more southern locales that Mercy works in, Atlanta for example, the issue is a lack of resources. Large quantities of luxury housing are being constructed as compared to low and moderate-income projects. Few public services are available to help individuals struggling to make payments. “The worst place to be is 61 percent of the area median income,” Graf said. “If you hit (past) 60, you lose availability of public programming…that housing is shrinking. There’s not a lot of for-profit developments that are developing mid-level.”

Part of the problem is sheer economics, according to Graf. The cost of land, cost to build, amenities and competition drive prices up. Graf predicted that at some point the market will become saturated and upper-end prices will fall off.

Mercy, on its end, has sought to combat inflated prices by managing its 21,000-unit portfolio in areas of greatest need. “Our motivation is that people need stability,” Graf said. “They can’t really control their lives without that stability. That is no way to live.” She added that issues such as education, healthcare and senior assistance all tie into affordable housing.

Graf and Mercy have gone about their goal of providing tenants with safe, quality housing and supplemental resources in two primary ways: bringing housing to areas with mass transit and resources and aligning such resources to existing units of affordable housing.

Mercy owns four properties within a five-block radius in the Visitacion Valley section of San Francisco. It is also redeveloping a large block of nearby public housing, tearing down and replacing 875 units on 50 acres of land with 1,500 units. The needs don’t end there. Graf noted that the neighborhood is a food desert in need of a grocery store, childcare services and affordable transit. In such cases, Mercy works with partners to bring such supplemental services to the community.

A Mercy project in Atlanta is taking an inverse approach. There, Mercy is building senior housing on a site adjacent to a shopping center and down the street from a Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) station. The site is being constructed in cooperation with a health clinic that will be located next door that will provide residents with medical care.

Terri Hamilton Brown, regional vice president of development Midwest at The Community Builders (TCB), echoed the various approaches for different areas concept. TCB is based in Boston and works in 14 states and the District of Columbia. TCB owns 11,000 affordable units, managing approximately 1,000 others owned by other nonprofits. The organization also works with residents around civic engagement issues such as local education.

“Our work can be different in different locations,” Hamilton Brown said. “You look for opportunities to develop, but they have to meet the needs of those areas.”

Cincinnati, Ohio has a distressed portfolio of historic Section 8 rental units that TCB has worked on restoring. TCB developers noticed an old shopping center that had lost its grocery store, so now efforts are being made to tear down the center and rebuild a mix-use development with businesses and residential units anchored by a grocery.

Up I-65 in Chicago, TCB is looking to start from scratch with a project on vacant land near the city’s South Loop, said Will Woodley, director of development in TCB’s Chicago office. The idea there, as with another ongoing TCB project in Chicago, is to weave affordable housing into market-rate developments and established neighborhoods.

Building mixed-income housing, not just redeveloping public housing, is a primary challenge today in cities such as New York, Boston and Chicago, Hamilton Brown said. Bringing diversity to downtown areas and resources such as proximity to work for individuals of more modest incomes makes sense on a number of levels, but there are plenty of challenges in making it work, she said.

Most housing and zoning policies are local. In cities such as Chicago and New York, public policy informs a desire to have a blend of market-rate and affordable units in developments. That priority might not be shared in the suburb down the road, however. From a zoning perspective, it is difficult to create developments in neighborhoods primarily comprised of those who own their homes.

There is also a lack of public support and policies supporting affordable housing. When TCB first expanded into Chicago about 15 years ago its redevelopment work on a group of housing known as Oakwood Shores was led by Hope VI, a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) program that no longer exists. Hamilton Brown said that there has been little indication from the new administration on how housing and urban development will be approached. An early effect has been that banks and investors have been less aggressive in recent months in making commitments for projects, forcing TCB into a wait-and-see mode.

Questions regarding what is to come under the new administration has put a freeze on tax-credit investing, added Dick Burns, president and CEO of the NHP Foundation in New York City. The main engine that drives both development and redevelopment is tax credits and tax-exempt bonds. Investment has dipped due to questions circulating regarding how tax credits will be valued in the future.

There are two additional drivers of the more substantial affordable housing challenges seen in recent years, Burn said. For one, there is the availability of existing affordable units. Existing units in need of rehabilitation are valuable, according to Burns, because it costs about 40 percent less to rehabilitate a property than construct a new one. Of the 1.5 million existing government-assisted units, about one-third are at risk of being lost due to owners opting out of affordability controls or failing to maintain properties. Taking hold of such properties is complicated because of private equity firms’ ability to buy up units and raise rents when controls expire.

Difficulty in competing with economic buyers for properties is exacerbated by the second challenge, financing. If an affordable housing developer is going to rent at below-market rates, then it can’t build or renovate at cost. Subsidies such as tax credits and HUD’s Section 8 voucher program are both vitally important and are both often targeted by Congress for reduction or elimination.

To get a better sense of need, the foundation recently commissioned two surveys with 1,000 responses each. In a survey looking at general needs, 65 percent of respondents reported that they were “housing burdened” — meaning that 30 percent or more of income is spent on rent or mortgage. Three-quarters of respondents reported that they fear losing their homes.

A second survey focused on Millennials found that 69 percent were housing burdened and 76 percent made housing compromises such as putting off saving for the future, moving further away from work or school and finding a roommate. A third survey is planned to focus on the needs of seniors, who battle through similar struggles on modest means, according to Burns.

Once units are developed or redeveloped, the onus is on preservation. That is where the foundation has focused its attention after building a portfolio of 8,000 developed or redeveloped units. HUD’s Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program has been valuable in this sense as it allows for housing agencies to apply for project-based vouchers on rehabilitation projects as opposed to developments.

When foundation leaders aren’t preserving, they are advocating and educating legislators about the importance of dwindling subsidies and efforts to improve conditions. A bi-partisan bill developed by Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash) and Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) has been a recent focus of foundation lobbying efforts. The bill would increase low-income housing tax credits by 50 percent, allowing for the creation or preservation of 1.3 million units during the next 10 years, 400,000 more than current credits would accommodate.

Once units are developed with tax credits, legal requirements generally dictate at least 30 years of affordability. In addition to being a finite amount of time, that span doesn’t include the fact that housing assets are in need of sprucing up and maintenance in the interim. A developer might be inclined to opt out after the 30 years and not maintain the property in the interim. This is the realm the National Housing Trust (NHT) works in, according to Michael Bodaken, president, and Scott Kline, vice president in charge of development. “We’re socially motivated. We are not interested in seeing [the units] get out of the program. We are constantly investing and evaluating assets,” Kline said.

Competing in the current housing market is challenging for nonprofit developers and preservers because there is a ton of cash in the market at the moment and investors aren’t having to go to lenders to move forward with projects. Even in cases when lending is necessary, market-rate developers are able to buy properties in New York City and Washington, D.C., under the speculation that rents will remain high.

NHT staff is unable to make such speculations and charge high rents, so they have sought other means of competing in the high-priced north and mid-Atlantic corridor. NHT is one of 12 members of the Housing Partnership Equity Trust, a social venture real estate investment trust. The purpose of the trust, according to Kline, is to be able to pool resources and move quickly on properties as opposed to having to come up with complex financing individually.

NHT has also secured a $20 million line of credit with a bank that allows for quick turnarounds as NHT staff are able to do the majority of the underwriting. An additional $10 million line of credit with the Kresge Foundation is expected to be closed on early this year, according to Bodaken.

Bodaken and Kline noted that the trust tends to target subsidized units that are large and do not deal with vacancy issues or non-subsidized projects that can be converted and maintained with the help of local partners and funding. The goal is continue to identify high-opportunity sites during this time of uncertainty.

“To grow what we’re doing, we need to buy in on certain opportunities,” Kline said. “The election was a big deal. There’s a lot of concern about what tax reform would mean for low-income tax credits. We’re pausing and spending a lot of time talking and thinking about ways to do our business that would accommodate if there are changes.”